RESULT AND IMPACT INDICATORS

The project’s activities contributed to the outcomes related to the components “sustainable production” (1) and “territorial planning” (3) of the Amazon Fund’s Logical Framework.

The main indicators agreed upon for monitoring these objectives were:

General Indicators

- Total number of Indigenous people directly benefited by the project-supported activities

Target: 2,179 | Achieved: 2,179, including 1,154 women

Direct Effect (1.1): “economic activities for the sustainable use of biodiversity identified and developed.”

Output Indicators

- Number of technical assistance visits conducted

Target: 84 | Achieved: 83

This target was not fully met due to the period of social isolation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Outcome Indicators

- Revenue generated from sustainable use economic activities (raw products – Brazil nuts)

Target: R$240,000.00 | Achieved: R$1,910,653.50

- Volume of raw production generated from sustainable use economic activities (raw products – Brazil nuts)

Target: 104,000 kg | Achieved: 780,115 kg

Direct Effect (1.2): “value-added forest product chains expanded"

Output Indicators

- Number of structures implemented for handicrafts and processing of agro-extractive products

Target: 18 | Achieved: 41

Outcome Indicators

- Revenue generated from processed products (handicrafts)

Target: R$10,000.00 | Achieved: R$4,250.00

- Volume of processed product generated (handicrafts) – production growth

Target: 10% per year | Achieved: 5%.

Direct Effect (1.3): “management and technical capacity enhanced for forest management, processing of agro-extractive products, and seedling production"

Ouput Indicators

- Number of Indigenous people trained in restoration of degraded areas, water resource management, and agroforestry systems (SAFs)

Target: 40 | Achieved: 73

- Number of exchange events on agroforestry and agro-extractive production techniques:

Target: 4 | Achieved: 4

Outcome Indicators

- Number of Indigenous individuals trained in degraded area restoration and sustainable production who are effectively applying the knowledge acquired

Target: 40 | Achieved: 73

Direct Effect (1.4): “degraded and deforested areas recovered and used for economic and ecological conservation purposes.”

Output Indicators

- Number of seed banks implemented

Target: 3 | Achieved: 2

- Number of nurseries implemented

Target: 3 | Achieved: 2

- Area restored through agroforestry systems (SAFs):

Target: 4.8 ha | Achieved: 50.55 ha

Outcome Indicators

- Area restored through SAFs (with more than two years of recovery):

Target: 4.8 ha | Achieved: 50.55 ha

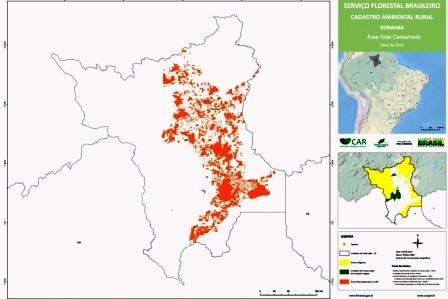

- Extent of Indigenous Lands under community protection and surveillance:

Target: 1,007,000 ha | Achieved: 1,007,000 ha

Direct Effect (3.1): “Seven Indigenous Lands in the Purus and Madeira river basins territorially protected.”

Ouput Indicators

- Number of Indigenous individuals trained in territorial surveillance

Target: 70 | Achieved: 73

- Number of Indigenous individuals trained in geographic information systems (GIS)

Target: 12 | Achieved: 73

- Number of GIS systems for territorial surveillance implemented

Target: 6 | Achieved: 6

- Number of surveillance expeditions conducted in the Indigenous Lands

Target: 21 | Achieved: 43

Outcome Indicators

- Extent of Indigenous Lands under community protection and surveillance

Target: 1,007,000 ha | Achieved: 1,007,000 ha

- Number of Indigenous individuals participating in territorial surveillance and monitoring in the Indigenous Lands

Target: 70 | Achieved: 73

Direct Effect (3.2): “Igarapé Preto Indigenous Land with defined territorial and environmental management.”]

Ouput Indicators:

- Extent of Indigenous Lands with defined environmental and territorial management (km²) – Tenharim do Igarapé Preto Indigenous Land

Target: 87,413 ha | Achieved: 87,413 ha

Outcome Indicators

See Direct Effect 3.1.

Institutional and administrative aspects

The presence of field technicians in the municipalities of Lábrea, Humaitá, Pauini, and Boca do Acre strengthened the relationship between IEB and its Indigenous partner organizations. Notably, with support from the Brazilian Navy, a nautical training and licensing course was promoted for 28 Indigenous participants, enabling them to operate their own boats - acquired through project resources - with autonomy and professionalism.

With the establishment of the field team in southern Amazonas, the institution adapted its entire payment request and approval workflow, improving its administrative and financial processes, as well as asset management, based on the acquisitions made through the project. The hiring of a dedicated financial manager enabled more systematic monitoring of both the project budget and the organization’s overall financial management. This successful experience led IEB to assign a financial manager to each program, ensuring greater efficiency in implementation and better coordination between programmatic and financial areas.

Another significant advancement was the infrastructure supported by the project in the territories - such as boats, computers, cell phones, Brazil nut storage structures, among others - which are essential for enabling communities to manage their territories effectively.

Risks and lessons learned

The hiring of a field team working directly in the municipalities enabled greater agility in implementing actions and strengthened dialogue with Indigenous associations and territories. This was a key factor in overcoming the logistical challenges of the region, which depends on seasonality and rainfall patterns to access communities and territories.

Another challenge faced was the COVID-19 pandemic, which hindered field activities. In collaboration with partner associations, new approaches were developed to ensure the continuity of activities, maintaining deliveries in the territories and promoting actions led by the communities, associations, and Indigenous Environmental Agents (IEAs) trained by the project.

The partnership with National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (Funai), established through a technical cooperation agreement, enabled integration with the agency’s decentralized regional units for implementing actions; however, this partnership was weakened from 2019 onward due to the political context.

Another lesson learned was the importance of combining different projects to achieve more significant results, such as the “Nossa Terra” project, supported by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

The lack of implementation of PNGATI by the federal government between 2019 and 2022 exposed the risks associated with discontinuity in public policy execution, which also resulted in the absence of new calls for proposals from the Amazon Fund to continue consolidating Indigenous territorial management in the region.

Sustainability of the results

The Indigenous partner associations have increased their capacity to directly access funding and manage their own projects, thanks to the institutional strengthening provided by the project.

The initiative enabled the formation of a network of Indigenous Environmental Agents (IEAs) who carried out territorial surveillance expeditions and implemented monitoring tools, including the creation of georeferenced maps developed by the trained Indigenous participants themselves. As a legacy, the project leaves behind a network of 73 IEAs equipped to manage their territories, while also presenting an ongoing challenge: to consolidate a permanent protection network in southern Amazonas.